Remember 2011. The Importance of a Year of Global Uprisings.

Introduction

Mark Fisher’s Capitalist Realism (2009) opens with the borrowed assertion that “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism”—it is a daunting statement, but one quite incredibly true. The signs of apocalypse are everywhere: the conditions that sustain human life on earth are endangered—air becomes unbreathable and water becomes undrinkable; new waves of reactionary nationalisms and religious fundamentalism fuel fear and hatred, leading to armed conflicts and the re-strenghtening of borders failing to keep out hordes of desperate migrants; core democratic values are being renounced in the allegedly more democratic countries; the burden of debt rises to the stratosphere; concentration of wealth and inequality are at levels that would have been unthinkable a century ago. These are only a few items of a long list of indicators that portray a world steadily in decline. Elite politicians around the world do show concern for these problems, but fail to show will or even intent to propose alternatives. It seems as if their stance is that of just avoiding as much as possible the negative consequences of these trends, because an attempt at halting, let alone reversing these, is not feasible. We are led to believe that there isn’t much that can be done politically in the context of a highly complex globalized world. It is not that apocalypse seems imminent, but that in being unable to conceive of a change of paradigm, we picture our society as walking towards the inevitable destruction of itself. We find ourselves at the end of history.

Yet this can’t be all there is. As much as doom dominates our society’s pessimistic fantasies, it is perhaps just a cynical tool for dealing with a reality that appears ungraspable. The wave of protests that shook the world in 2011, however, was an important reminder that people do hope for a different state of affairs. It showed that despite the apparent political apathy that is characteristic of our era, spontaneous collaborative organization that demands change is very much possible, and that it can quickly transcend national and cultural boundaries. It was also a reminder of another important aspect: that at present, when there is a strong popular impetus to reorganize society in a way more just, it is forestalled by the lack of particular ideas that are able to combine the reality of our globalized world with a more just and ecologically responsible society. Such lack has very negative effects for democracy, as it stagnates debate and ensures the status quo of the powerful; recall Margaret Thatcher famously stating that “there is no alternative”. But surely there has to be an alternative. How do we set about trying to identify such alternative, or an array of alternatives, that help us direct our efforts towards a society that dreams more sympathetic dreams than those of apocalypse?

Chapter 1: 2011 & The Rebirth of History

The financial collapse of 2008 was significant not only for the sheer magnitude of its reach and consequences, but also for how it served to illustrate the perils of two trends that had been experiencing exponential growth for the last three decades: globalisation and the financialisation of the economy. For globalisation, it showed the extent and rapidness in which events can spread from a single significant location (Wall Street), to affect almost the whole world—with the consequences of these events being felt almost simultaneously between the epicentre and the periphery. For the financialisation of the economy, as the most common metaphor runs, it meant the burst of a bubble; a bubble that had been allowed and encouraged to grow so big and intricate that it was well beyond any level of human intelligibility, hence out of human control. But these two trends, far from being casual, were the essential processes promoted by the on-going project of global neoliberalism that started in the 1980s. Thus, the third significant revelation of the crisis was that of the failure of the promises of neoliberalism: that a worldwide free-market arrangement would lead to infinite growth and the end of ideological chasm.

For the first time in perhaps decades, the western political elite were faced with a real political challenge. As Naomi Klein (2015) argues, this was a point in which, despite the severity of the crisis, a window of opportunity was open for a top-down political project to enact an ambitious change of paradigm. On the political level, there had been a gradual concession of sovereignty from nation-states to supranational, undemocratic bodies that increasingly curtailed parliamentary regimes from taking significant decisions. On the economic level the concession was towards privatisation; huge instances of the economy previously regulated by the state had been trusted to the private sector to manage. The blatant failure of these two processes should have provided an incentive for national political representatives to ‘stand up for their people’, by displaying a will to take action to defend the interests of their citizens; and not those of extranational institutions that instructed them otherwise. But as is now evident, this was not the case. Instead, the political elite doubled down on the neoliberal project, putting the resilience of the markets before the wellbeing of their societies. The citizenry watched as their leaders called on them to ‘tighten their belts’ (for they ‘had lived beyond their means’), while those really responsible for the situation either stayed in their posts or walked away with obscene bonuses—at the same time in which the institutions they had led to collapse were being bailed out with unheard-of amounts of public money. Except for a few exceptions that include the nationalisation of banks, Obama’s Dodd-Frank Act or the half-hearted trials of a few top bankers, the system was left untouched, reinforced even.

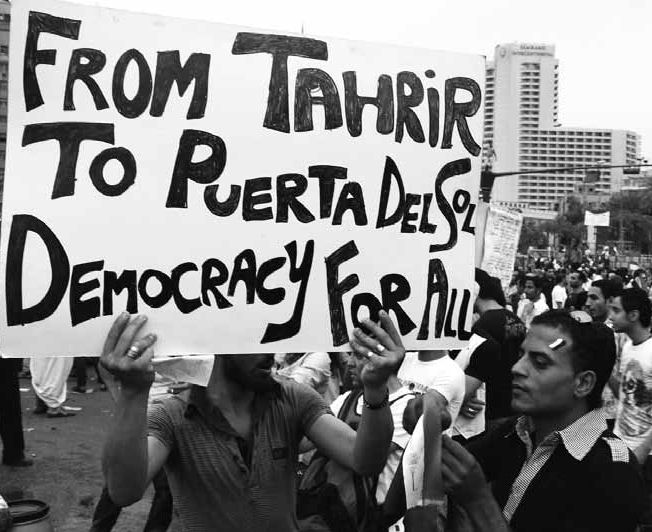

The project of neoliberalism and its crisis astonishingly achieved to undermine border constraints, ever thriving through all forms of political designs; whether it was liberal democracies or authoritarian regimes. And just as these phenomenons were global in reach, so were the cycle of protests that emerged in 2011. In the earlier dates of that year, civilian uprisings in North Africa and the Middle East took to the squares and in the space of a couple weeks achieved to depose long-standing dictators, as in the most notorious cases of Egypt and Tunisia, and sent heat waves of protest to the rest of the world. Soon the European Mediterranean countries (Spain, Greece, Italy) perceived the uprisings of the Arab world as a call to a struggle that, despite some important differences, was a common one. The wave of protests continued to expand during the year (to Chile, the United States, China), and on the 15th October, almost all major cities in the world had demonstrations which, albeit each having a particular name (Occupy, Indignados, 6 April, etc.) explicitly alleged to the same global call. In this aspect, it can be argued that the global wave of protests that the world saw in 2011, shared significant qualities with the financial collapse three years before. Both were situations for which it was difficult to find precedents; just as the financial collapse, the speed and extent of the insurgencies were largely unexpected, even to the activists and organizers of the demonstrations. Also similarly, a key factor of this rapid expansion was the generalised use of communication technologies that allow blurring the constraints of time and space.

This cycle of struggles was a global event of significant importance. Many have drawn comparisons between the events of 2011 and previous ones pertaining to the ‘anti-globalisation’ movement by the turn of the century, which include the well-known protests of Seattle, Gothenburg and Genoa. However, even as the two cycles of protests shared some of the main struggle premises (increasing power of supranational bodies and their undemocratic practices), those of 2011 constituted a new paradigm. Despite the political contingencies of each country in which these protests happened, this was the first time in which there was a global spontaneous and simultaneous response, largely targeting neoliberalism’s apparatus of discourses and practices as the root cause of many evils; from political corruption, to income inequality, to the threat of climate change. But perhaps more distinctively, there was also positive generation: firstly, that of a new universal subjectivity of ‘the people’, and secondly, a call for rethinking the globalisation project—not outright rejecting it it, but actually taking up the task of making such project one that is inclusive and non-destructive. It will be argued here that the former of these characteristics was successfully achieved, and with great importance, but that the latter was not; which led to the eventual demise of the protests and in many cases to a nationalist-populist turn.

Following the wave of protests of 2011, in the course of that year and the next, many relevant contemporary philosophers (including Zizek, Hardt & Negri, Chomsky, Badiou, Berardi, Castells and others) published short books with their reflections on the events—a fact which alone speaks of the importance of these. Alain Badiou interestingly named his book on the matter The Rebirth of History: Times of Riots and Uprisings, ironically placing it against Fukuyama’s 1992 well known The End of History and the Last Man. Fukuyama’s death sentence on history was informed by the belief that humankind had reached the zenith of political organisation with western liberal democracy and (the now unstoppable) global capitalism. But when Fukuyama published his book, following the fall of the Soviet Bloc, it was not only the scholars’ view that the new paradigm of unfettered global capitalism was somehow an end-stage of history; as Franco Berardi recalls, the subcultural movements at the time also seemed to evoke a sense of hopelessness, epitomised by the punk rock scene with the Sex Pistols screaming ‘No Future!’. For a considerable amount of time, in Europe probably since the revolts of 1968, there hadn’t been a significant culturally insurgent movement; one that could engage in the stimulus of significant political debate—much needed in a time where the agenda for the future of the globalised world was being set. Whether it was complicity or contempt that different social groups felt towards the forming new world, there seemed to be a shared acceptance of the inevitability of the processes in place. 2011 meant the reversal of a cycle of stagnation in the citizenry’s capacity to imagine and articulate ideals to defend in the political arena.

The most important protest nuclei of 2011 were part of the same politico-philosophical event, one of utmost importance, a call for ‘the universal freedom of humanity’: performed in unplanned, spontaneous encampments in the physical hearts of each country and appealing to one Idea of love, justice and dignity present in the heart of every human. Regardless of the readily observable outcomes after their eventual demise, and also of the previous grievances that had built up the social unrest, these protests deployed a Platonic Idea of the good in a universal and timeless form, and the event of this invocation is by itself incorruptible, albeit volatile. (Zizek, 2014)

For Badiou, these protests, where they were significantly large, are to be considered ‘historical riots’: of an intensity and transcendence that goes beyond those of more common ‘immediate’ and ‘latent’ riots. An ‘Immediate riot’ is a quick response to a particular display of violence (either abstract or physical) by the state or predominant power, in which the youth loot and destroy symbols of power and wealth in the outskirts of the metropolis. These riots stagnate in their own social space without transcending it, and are met with great hostility by the public opinion—the English riots of 2011 and those of the Parisian banlieues in 2005 fit this category. ‘Latent riots’ start as a response to an on-going particular problem, be it a law reform or a corporate wrongdoing, and their importance lays in their capacity to erode the subjective divisions normally imposed by the state and trade unions, creating a new subjectivity that includes people of all walks of life: students, unemployed youth, low-skilled wage-earners, specialized professionals, intellectuals, elders, etc. Despite this achievement, these do not form the basis for a potential uprooting of the existent power structure and its replacement for something else. A historical riot does. It is characterised by a threefold process of localisation, contraction and intensification. Unlike the immediate riots, a historical riot is ‘localised’ in that it manages to set itself in a core public space of symbolic value (like Tahrir Square in front of the Mogamma or Zucotti Park in front of Wall Street) and it stays there, conquering it, setting up camp for an indefinite period. By ‘contraction’, it takes the potential of the latent riot in eroding fragmented identities and generating a new subjectivity of ‘the people’, inclusive of all those not pertaining to the ruling elite; but it takes it one step further. The historical riot has a special quality in that those who are there in the square demonstrating, somehow come to represent the whole spectrum of the people. Badiou notes how western governments and media named the protesters in Tahrir square ‘the Egyptian people’—even though there weren’t more than one million people (out of eighty million Egyptians) at any single time rallying in the square, the protesters had generated and engulfed a subjectivity that was felt as ‘the legitimate Egypt’ in the eyes of the rest of the world. The ‘intensification’ comes as the insistent activism and militancy of the protestors has the capacity of generating an essential and undisputable ‘truth’, that of “the Idea, the very being of the people, what people are capable of as regards action and ideas”. This truth that emerges from the historical riot is one “that enthuses everyone, just like the finally discovered proof of a theorem, a dazzling work of art or a finally declared amorous passion—all of them things whose absolute law cannot be defeated by any opinion.” (Badiou, 2012:61)

Thus, what such events generate is the essential possibility of a reopening of history: the new subject of the people defines itself spontaneously, but also explicitly, apart from the state, and in its own truth it gives itself absolute legitimacy and authority to express a positive vision, also apart from the state or any existing power structure. And this is, for Badiou, the essential importance of the events of the Arab Spring; “that a revolt against state power can be absolutely victorious” is, especially for a western audience, “a teaching of universal of universal significance”. (2012: 108)

It is a recurring theme in the criticism of neoliberalism that it erodes the capacity of society to be politically active, as it erodes politics altogether. This it does by design at the level of national and supranational governments: whenever a political project divests from the interests of global capital (commanded by the IMF), it is called out as insensible populism and put down. But at the smaller scale of the everyday life of the citizenry, the mechanisms that prevent individuals from engaging with politics are more subtle. Invisible alienating forces pervasive in today’s culture prevent the public from realizing alternative ways of relating to each other and reaching a sense of commonality. Identities are defined not in the belonging to a community, but in people’s choices as consumers. Disparate identities are thrown onto individuals and demand to be satisfied by them at each turn. As individuals focus on thriving in these unstable identities, notions of the common good fall out of sight (Bauman, 2000). Because we are enclosed in our bodies and names, which themselves become commodities, we have no motive to act with solidarity instead of self-interestedly. And at the same time, as our debt piles up, the patience that would be necessary to stop and rethink life’s meaning and the best possible way to live it out is not available. The speed of information and of financial trading is such that there is no time to invest in such an effort. Michael Hardt and Toni Negri consider that:

The triumph of neoliberalism and its crisis have fabricated new figures of subjectivity […] The hegemony of finance and the banks has produced the indebted. Control over information and communication networks has created the mediatized. The security regime and the generalized state of exception have constructed a figure prey to fear and yearning for protection—the securitized. And the corruption of democracy has forged a strange, depoliticized figure, the represented. (Hardt and Negri, 2012: 15. Emphasis added)

The subjectivities deployed by the apparatus of neoliberalism effectively displace any possibility of political engagement from the citizenry—for an entire generation, the democratic promises of liberal constitutions (sovereignty lies with the people) seem like the pleasing but nonetheless futile floral decorations of corinthian columns. Thus, the first task of a revolt at present (understood as any form of popular upheaval seeking to upend the status quo), is to expose these alienating subjectivities, putting them in question, and thus attacking their immanent character. In fact, taking a look at the most recurring slogans of the encampments and occupations of 2011, it is readily observable how this was being done.

These four ‘categories of alienation’ as they might be called (debt, media, security/fear, and political representation) were in fact blown up by the protestors, and in denouncing them they also made them visible. On the debt front, the severe austerity measures being imposed on the basis of a supposed ‘overspending’ of the welfare state in years prior to the crisis were called out as aberrant, deeming the indebtedness of the public as illegitimate—suggesting public audits of the debt and even demanding default on external public debt. In relation with the media, the protestors came to learn first-hand how their actions and overall ethos were manipulated to fit narratives convenient to the predominant power structure. After some time some of the media started to sympathize with the protestors, but it was only after the persistent demonization of these was no longer credible to the audiences at home. For the constant state of exception which the world lives in after the events of 9/11 (especially in the western world), the protests managed to breach the paralyzing fear and paranoia that looms over a society which increasingly resembles a police state. The protesters themselves were tagged as terrorists at first, but they could also learn first-hand how the police used explicitly terror-inducing methods on them (amongst the civilians were many elders and children), realizing thus that the fear is on the side of the elites, which feel the ground under their feet tremble. Finally, there was strong emphasis on how the political class had grown distant from those they supposedly represented, thus the protesters called into question the whole apparatus of representative democracy—and there was contempt about the viability of political representation; with explicit intent, effort was put at first in emphasizing the non-reducibility of the movements into parties or leaders.

The power of a mass uprising is this: it can subvert overnight many of the alienating mechanisms by which society and individuals lose their power in face of states, corporations and supranational institutions, and reclaim the symbols that sustain any form of large human organization. Legality, sovereignty and legitimacy: all these shift in a moment from residing in the imposing palaces of government (and the back-offices of the bigger banks) to being shared between the people in the square shouting at once. This extraordinary shift might be reverted at some point and return to where it was previous to the uprising; but however short-lived this experience might be, it retains its immense force in that it has proven that a despotic state is only a consented monster, never an irrefutable metaphysical category. The people (which on that level, do constitute a more valid element of the real) can, at any given point, reclaim that the alienation of the aforementioned symbols be brought back to the ground. The events of Egypt and Tunisia were the ones that exemplified this more clearly. With the clear and concise messages of ‘Mubarak get out’ and ‘Ben Ali dégage’, the people came to enact their sovereignty; and it was felt immediately by these authoritarian presidents, who in the space of weeks left their long-held posts in face of the irrefutable lack of legitimacy.

As has been noted, the circumstances, intensity and outcomes of the cycle of struggles of 2011 varied from one location to another. Some achieved little more than a riotous momentum that hardly pointed to any form of articulated political statement, while others were so successful that managed to overthrow governments. Nonetheless, a characteristic common to all these movements was that they succeeded more in pointing to that which was to be rejected (the marriage of finance with politics, the dismantling of the welfare state, despotic and corrupt politicians and so forth), than in the formulation of positive proposals. The act of saying no is powerful, but if its potential is realized, then it needs a subsequent yes. In face of the absence of directions for that second step (which will be reflected on in the next part), there is a twofold risk. The first is that the powers that be retake control of the situation and come out reinforced, as the momentum of the uprisings fades away. The second, more dangerous one is that the void left by an upheaval that has exposed the ruling elite’s wrongdoings but has failed to provide with a plan for change may be taken up by populist opportunists that claim to have those answers.

Slavoj Zizek likes to cite Walter Benjamin’s assertion that behind every rise of fascism there is a failed revolution. To him, as to many others, there is a direct correlation of the social unrest that led to the events of 2011 and the new advent of far-right parties in almost every western country. Five years later to the protests, in 2016, discourses demonizing migrants, extolling patriotism, invoking a glorious nationalist past and so forth managed to capture the attention of the majority of voters, achieving victories in the bedrocks of liberal democracy that are the United States and the United Kingdom—and in other countries where right extremists didn’t win, as in the Netherlands and France, they still managed to come second, which would have seemed unthinkable just five years ago. However appalling these results are, they shouldn’t come as a surprise.

One of the most recurring slogans of the demonstrations of 2011, as Manuel Castells (2012) recalls, was the loss of dignity. In fact, in a recent talk at Goldsmiths by Yannis Varoufakis and Danae Stratou about the importance of re-involving art with politics and viceversa, they presented an art project in which they asked the Greek people to describe their main concern in one word: ‘dignity’ overwhelmingly came out as the most stated. Will Davies then astutely inquired them about the danger of such a feeling—whoever poses to restore that dignity, he argued, might gain popularity very quickly, and ‘dignity’ is in fact often a central slogan of the nationalist far-right. And this is precisely what we are witnessing not only in the western world, but also in the Middle East and elsewhere: reactionary feelings are being activated as a shield against the loss of dignity.

It is not difficult to understand where this perceived loss of dignity comes from. The traditional political antagonisms of western democracies since the second world war, between more socialist leaning democrats and more conservative liberals, have been insignificant for the past decade, for irrespective of what party was in power, the policies would be the same, especially in economic matters. This has caused great discontent among the electorates, who have seen their quality of life significantly reduced in a short period of time with no prospect for the reversal of such trend. As has been argued, the observable paradigm of governance in neoliberalism is one in which politics is devoid of content; all that governments are really concerned with is the frictionless unwinding of the ‘free market’ economy. This was clearly exemplified when, in face of serious economic crisis in Italy and Greece (which calls for serious political initiative), the European Commission, following command by the IMF, decided to remove politicians and appointed former Goldman & Sachs bankers as ‘technocratic’ presidents. It is in this context where UKIP’s Nigel Farage’s interventions in the European Parliament denouncing such practices as an assault on democracy gained millions of views on Youtube, and gradually brought him and other ‘euro-skeptical’ politicians to the fore. Faced with the establishment’s reduction of politics to technocratic management, the discourses of far-right politicians calling for a return to national sovereignty are, to a huge part of the public, a glimpse at true political will. Equally, the rise of Islamist political discourse becomes an appealing way of curtailing a eurocentricly commanded global capitalism. The gaining acceptance of these discourses has to be understood then as the condemnation of a political scene that has grown distant and alienated from people’s concerns. Amidst the lack of sound responses to the difficult economic and social situation, which are not available for the traditional left nor the right, the simplicity of the claims advanced by these populists, feeding off the negative feelings of the population (fear of terrorism, economic instability, lack of employment, loss of values), give the semblance of a positive plan in the guise of a return to some kind of ‘purity’ or ‘glorious past’.